Every clear night for the past three weeks, Bob Stephens has pointed his telescope at two stars in hopes of witnessing one of the most violent events in the universe—a nova explosion in a hundred thousand times more than the sun.

The eruption, which scientists say could happen any day now, is piqued the interest of major observatories around the world, and promises to advance our understanding. of turbulent binary star systems.

However, for all the high-tech observational power that NASA and other scientific institutions can muster, astronomers rely on many astronomers like Stephens to see this explosion first.

The reason? It costs a lot of money to keep their assets focused on one topic for months at a time.

“I think everybody’s going to watch it happen, but just sitting there watching it isn’t going to make it happen,” said Tom Meneghini, the observatory’s director of operations. – far from the most prominent chief executive at Mt. Wilson Observatory. “It’s like a watched pot,” he joked.

The star is so distant that it takes 3,000 years for its light to reach Earth, meaning that the explosion occurred before the last pyramids of Egypt were built. It will appear almost as bright as the North Star for just a few days before disappearing into darkness.

Once it’s spotted, some of the world’s most advanced sites in the world and in space will join in the viewing, including NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope.

“A lot of people are eagerly waiting to see the new jewel in the crown,” said Mansi Kasliwal, a Caltech astronomy professor who plans to use the Palomar Observatory in northeast San Diego County to observe the event. The nova will explode in the constellation Corona Borealis, or Northern Crown.

Steve Flanders, services coordinator for Palomar Observatory, shows off the Gattini-IR telescope, which Caltech professor Mansi Kasliwal will use to observe the explosion of the star Blaze.

(Hayne Palmour IV / For The Times)

T Coronae Borealis, also called the Blaze Star, is actually two stars – a hot, dense white star, and a cool red giant.

The young star, which ran out of fuel long ago and collapsed to about the size of Earth, has been drawing hydrogen gas from its massive neighbor for nearly all of human life.

This stolen gas has collected in a disk that surrounds a small area like the hot, dirty version of Saturn’s rings. Soon, the disk will become so massive that it will become violent and uncontrollable, and inevitably, it will explode like a thermonuclear bomb.

However, no star is destroyed, and this process repeats itself approximately every 80 years.

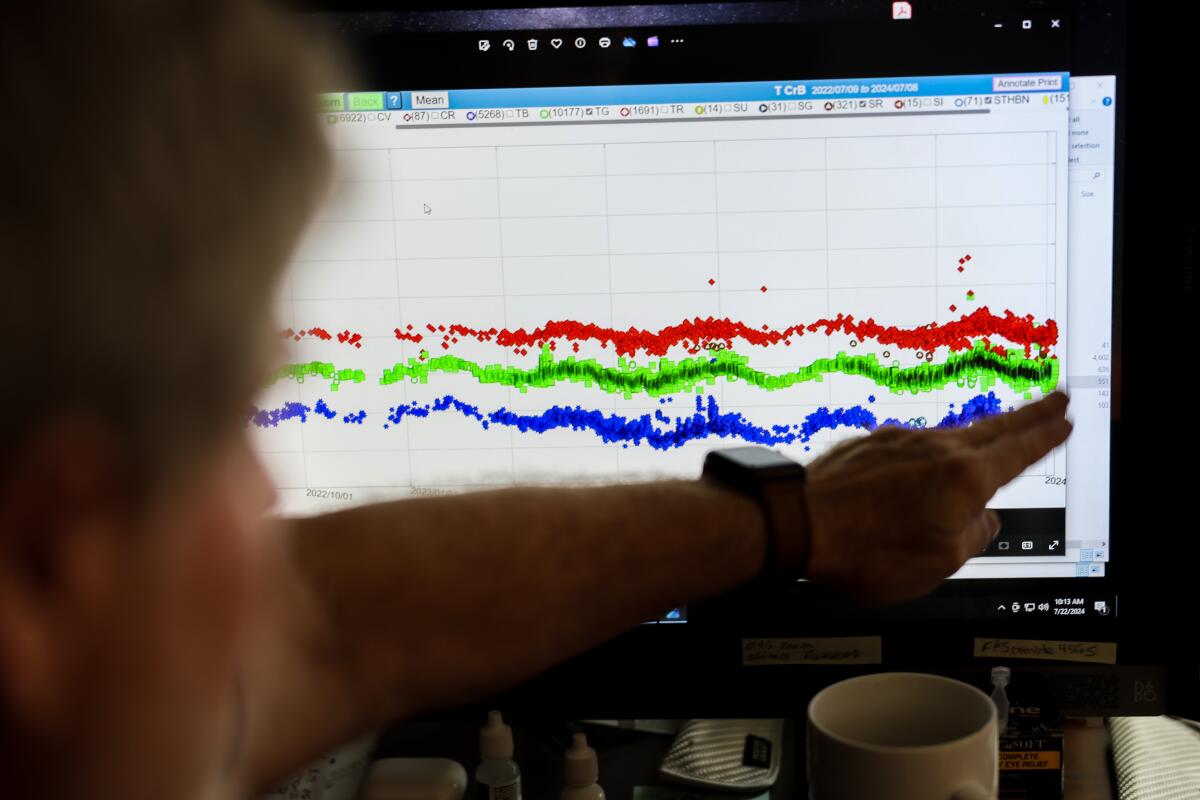

Stephens has data from T Coronae Borealis from years ago. The data oscillations represent two stars orbiting each other.

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

This time, there is an army of enthusiasts like Stephens ready to sound the alarm when a star goes nova.

Unlike hobbyists, many of these lay observers have published their scientific research. Stephens even built his own observatory as an addition to his home in Rancho Cucamonga.

“The city thinks it’s a sunroom,” Stephens said. After the inspector stood up, he removed the screws securing the roof, allowing him to open it up so he could see the clear sky through his telescope.

Every night, he turns on the telescope and spends more than an hour taking data, which he then sends to an online community of rare astronomers who monitor the nearly unknown star. stop.

It is absolutely impossible for large observatories to keep such a watch. Hundreds of astronomers compete for time to observe a wide variety of target stars each night. To them, keeping these telescopes attached to Blaze Star is a waste of valuable viewing time.

Estimates of when the nova will occur vary, but most astronomers agree that it will happen before the end of the year, and probably in late August.

Once it blows, there are several warning systems set up to notify laypersons and professionals alike. Some experts have even programmed their telescopes to abandon their current observation plan and look at the star when the announcement comes in, Stephens said.

Large observatories also face another problem. Most of their telescopes are designed to look at faint and dim targets, but the Blaze Star nova is no slouch. Pointing these telescopes at the nova would overwhelm the sensors, resulting in a washed-out, overexposed image.

That’s why Palomar Observatory, a Caltech research facility in northern San Diego County, doesn’t use the Hale Telescope, which has a 16-foot-wide image below its great white spot. Instead, it uses a very small telescope, called the Gattini-IR, located in an unassuming little brick building about a quarter of a mile down the road.

Once the nova occurs, Gattini-IR will go from observing the Blaze Star every night to a few hours.

Steve Flanders enters a small building on the grounds of the Palomar Observatory where the Gattini-IR telescope is installed. The Gattini-IR telescope is looking at Blaze Star, which is expected to start again.

(Hayne Palmour IV / For The Times)

Scientists say they still have a lot to learn about novas. For example, physicists still don’t know exactly why some things explode every ten years while others may not thousands of years.

Some researchers suspect that novae such as Blaze Star may be precursors to supernovae. These explosions – billions of times brighter than the sun – destroy the star, often leaving behind a black hole. Supernovas are also a useful tool for astronomers to measure space.

However, studying similar phenomena has led to discoveries.

Recently, scientists concluded that novae tend to throw material into the atmosphere at a greater speed than would be expected from the force of the explosion.

“We want to understand the physics of novae, so having a nova as close as T Coronae Borelias, which will hopefully be well studied by all the telescopes… we can get a complete picture,” said the Caltech professor. Kasliwal.

Some of that understanding will be due to untrained astrologers.

Because of the rapid development of telescopes, scientists are working with technology that scientists didn’t have 20 years ago, let alone 80, said Forrest Sims, an astronomer. of Apache Junction, Ariz., also has his sights set on the star. at night.

And lay people can get better coverage than big telescopes because “we usually have full control over when and where to point. [our telescopes],” Sims said. “An expert may have to write a grant to get half an hour or two hours at a large telescope.”

That allows them to collect more information. And with hundreds of people in the community watching from around the world, they can catch up on Blaze Star’s almost continuous content. Many, including Sims and Stephens, send their information to American Assn. on the Variable Star Observers websitewhich allows everyone to use the data.

Stephens remembers reading a newspaper article from an expert who was able to see five constellations in two years. “I thought, I can do that in a month,” Stephens said. He went on to publish a paper with 10 comments.

In his home studio, Bob Stephens uses a Borg telescope 101. “Resistance is futile!” Stephens said as he introduced the telescope, a reference to the phrase used by the “Borg” in “Star Trek.”

(Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

One professor was so amazed by the amount Stephens was able to see that he reached out and agreed to fly to Puerto Rico for an astronomy conference just to meet him. They ended up working together – Stephens had binoculars; he had connections in the field.

Today, the work of astronomers is so complex that many in the field find it hard to call them laymen.

Sims said: “We call ourselves ‘little scientists with telescopes.’ “It sounds more fun, and in some ways, experts will – even reluctantly – agree that the work we do is often of a higher standard.”

#star #explode #opportunity